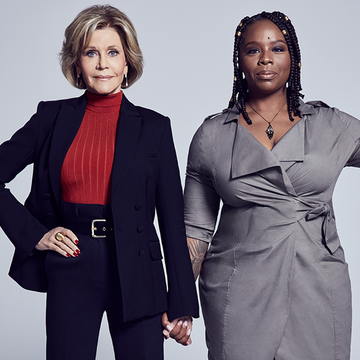

The new generation of #WomenWhoDare are those who refuse to conform. They dare to do the impossible, encouraging young visionaries to break—not just push—boundaries, inspiring people around the world to fight for what they believe in. Here, writer Jenna Sauers interviews model and activist Halima Aden for our 2017 Women Who Dare series.

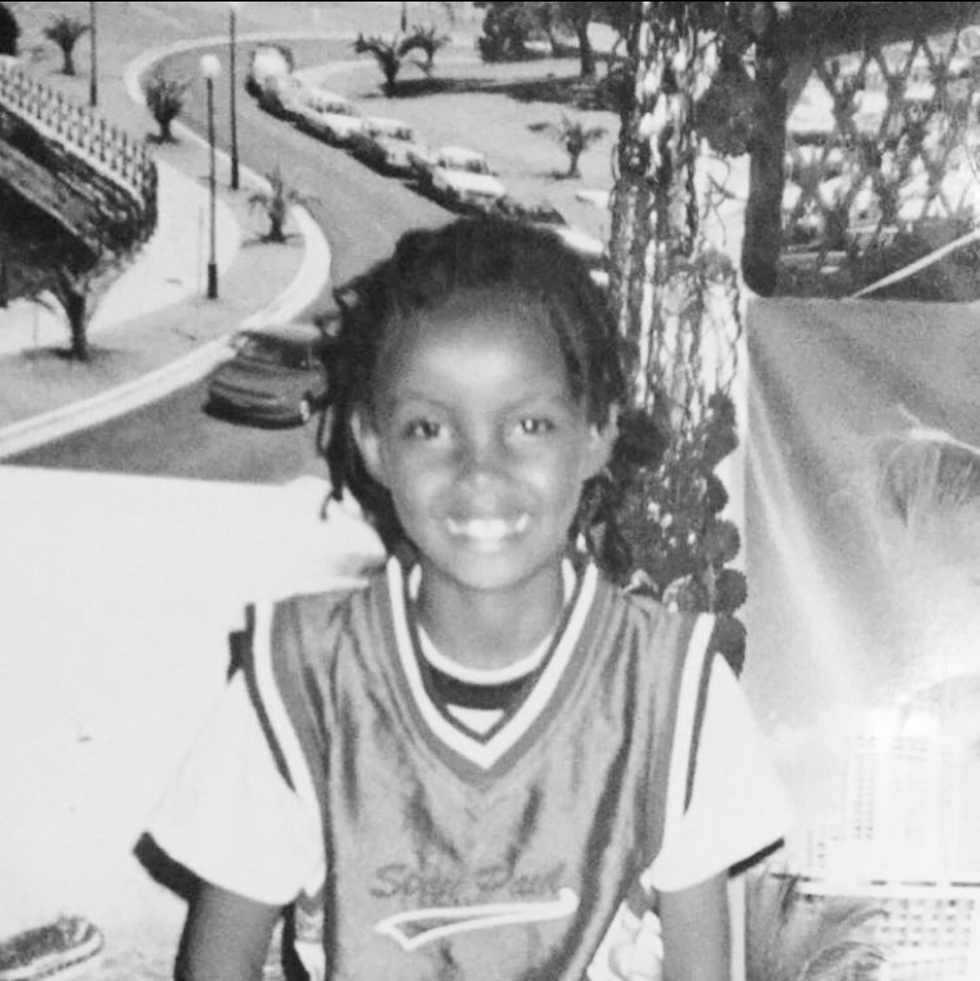

Halima Aden was born to Somali parents in a UN refugee camp in northeastern Kenya. Her parents had fled the fighting in Somalia after Aden’s mother’s village was burned to the ground in the early 1990s. Aden lived in the Kakuma camp while the family’s refugee application was vetted, a process that took almost a decade.

Although the camp’s dangers included wild dogs with rabies, tensions between different groups, food insecurity, and the risk of fire and flood, Aden remembers her early childhood as mostly a happy time. Her Christian friends would celebrate the Muslim holiday Eid with Aden’s family, and she would celebrate Christmas with their families. She also made friends with kids from the local Turkana ethnic group who lived in the region outside Kakuma and visited the camp to sell camel milk. The Turkana believe in a God called Akuj, and for a while, Aden did, too. “This local kid was always telling me, ‘You can't ever tell a lie because Akuj is always watching,’” she recalls. “When I was six, I believed in Akuj.”

When Aden was seven, her family finally received permission to resettle in the United States. At first, they tried St. Louis, but the family had difficulty integrating. They eventually made their way to St. Cloud, Minnesota, a small city that became host to a large Somali diaspora community beginning in the mid-1990s. In St. Cloud, Aden was elected homecoming queen—becoming the first Somali American to be part of homecoming court at her high school—and successfully campaigned for a student senate seat in her first semester of college at St. Cloud State (she’s currently taking the semester off school to concentrate on her career).

Aden shot to prominence in 2016 when she entered the Miss Minnesota USA pageant. She was the first beauty pageant contestant in the U.S. to wear a hijab. Photos of her competing on stage in her hijab and wearing a burkini (a swimsuit with pants and a long-sleeved tunic, plus a head covering) for the swimwear part of the contest were published in newspapers and blogs all over the world. While Aden didn’t place in the pageant, she did catch the eye of a modeling agent. Her career so far has included runway appearances for Yeezy Season 5 and MaxMara, and a campaign for Nike. Her first ever photo shoot was with Mario Sorrenti, and Carine Roitfeld has booked Aden repeatedly. Aden also has a burgeoning career as a public speaker, telling her life story to school and college students.

While there have been other Muslim models to make a name in the fashion industry—including fellow Somali Iman, Kenza Fourati, Imaan Hammam, and Hind Sahli—Aden is the first Muslim model who chooses to wear a hijab and dress modestly while on the job. The 20-year-old spoke with BAZAAR.com by phone from her home in St. Cloud to talk about the value of diversity in fashion, her dream of being a UNICEF global ambassador, and why she’s fine saying “Thanks, but no thanks” to any job that would require her to change her values.

Harper's BAZAAR: Does your decision to dress modestly and wear a hijab affect the kinds of modeling jobs you can do and the clients who book you?

Halima Aden: I’m not gonna lie to you, that was something that really stopped me from doing shows this season, and I was starting to feel really beaten down. Because I was hearing, “You were put on option for this, and this, and this…” I had four different options. They were all people who I was dying to work with, but it came down to wardrobe. This season, there just wasn't much I could wear, because it's spring season clothes.

The MaxMara show was such a blessing this season, because I came in, and on the board the designer showed me photos of the looks he wanted me to wear and I said, “Is that a hijab?” And he said, “It is a hijab, because I specifically had you in mind for this.” That experience this season really reminded me that I'm doing the right thing. I don't need to change myself.

A lot of Muslim girls and girls who wear modest clothing follow me on social media, and they were just as anxious and as excited for this season as I was. They were beaten down, too, when I wasn't walking at any shows, and people kept sending me pictures of runway looks, like, “You could have walked in this show! They could have paired this outfit with this outfit.” It was really cute, but that's now how the world works. And I'm okay with that. The truth is, I'm okay with never walking again. I'm okay to never do another modeling job again. When MaxMara happened, I posted a photo and I said thank you for keeping my wardrobe requirements in mind. And this girl commented, “He keeps you in mind, he keeps us in mind. Now this Muslim shopper will keep MaxMara in mind.”

HB: What are your wardrobe requirements, specifically?

HA: There is not a right or wrong way to dress as a Muslim, but for me, I don't wear pants alone, I wear something over my pants—a skirt, or a dress. I wear long sleeves. And then I wear my hijab. What I wear can't be too form-fitting. It's hard. But it's not impossible. In fact, it just forces people to be creative.

HB: Last year you made headlines by competing in the Miss Minnesota USA beauty pageant while wearing a hijab, which led to you being discovered as a model. What made you want to enter the pageant?

HA: I wanted to do the pageant because you can get scholarship money, and I wanted the chance to meet other women from all over Minnesota. 2016 was very divisive. That year, our president came to Minneapolis, he came to Minnesota, and he stated that the Somali community was a problem. I wanted to take the opportunity to meet other women who were going to college, who were looking for the same things that I was, and show them that we're a lot more similar than you would think. We come from different places, but we have a lot more things in common than we have different.

I also wanted to compete in the pageant without changing the rules—to not bend the rules, and still uphold my values. That's the thing, the stereotype is that Muslims want to come to this country and they want to change the rules, they want to change everything. That's the opposite of what I want. I just want to participate.

HB: The Star-Tribune reported that your mother was initially not thrilled about you doing the pageant.

HA: My mom holds education in such a high regard, and that's why she was against the pageant, at first. People were also coming to our house and telling her things that weren’t true. People were like, “Your daughter's going to have to change. What do you mean she's going to wear a hijab at the pageant? That's not true. They don't allow it.” People were convinced I couldn't do it, because they'd never seen anyone else do it.

HB: How do people in your community see your modeling career now?

HA: You would think that people learned from the pageant that you could do things like this, but even with modeling, they were like, “Now for sure she's going to throw away the hijab. Now for sure they're going to make her take it off.”

I've done enough shoots now, and enough things have come out, that I can show my mom how I'm being dressed and styled. It doesn't change the fact that she still wants me to quit all of it. If she could have it her way, I would be quitting tomorrow and going back to university. That's totally respectable. I understand. She doesn't put value into this newfound career. She puts value into education, and my getting an education was a lifelong dream that kept her sane through the years in the refugee camp, and through the long process of coming here.

I understand where she's coming from, and I understand her intentions, and I'm grateful that I do have a mom who values education so highly. Who tells me I can say no to all of this, no to fame, no to money, no to everything, because let's be honest, in a lot of cases, it's the other way around. Parents are pushing their kids into whatever—to go and get that record deal, or that basketball career, be a model, act. I understand and I'm grateful that my mom is really looking out for me. My mother knows that in life, you can lose everything. It can all be stripped of you. But to her, the one thing no one can take away from you is what you've learned.

I tell her that you also can’t lose experiences. And that's exactly what modeling is. It's new experiences—it's not just vanity and looking pretty. I think that for a very long time, women like me have been kept out of the conversation. We were talked about, but we weren't really given opportunities to talk for ourselves. This is my opportunity to draw my own narrative, to really tell people, this is my life, and I'm just as much of an American as any of you are. I look a little different, but it doesn't change the fact that I still call this place my home.

HB: What does the idea of representation in fashion mean to you, and how important is it?

HA: Oh my gosh, it's huge. When you are represented, people take it for granted. To understand the importance of representation you have to ask people who've never felt like they were represented fairly. For me, anytime I saw somebody who dressed like me in a movie, the character was someone oppressed. There was just a narrative to it that didn't match mine. Same thing with the news. Every time I saw somebody who looked like me, chances were they were doing something bad. Now, I get to represent my community to the majority.

The thing I hope I never become is the token girl. In magazines when I was growing up, you’d see it all the time, these shoots with four white models, and then one African American model, or one Asian model. That was their idea of “diversity.” You don't need to stop at just one. You can pick beautiful women from all walks of life!

HB: What was daily life like in the refugee camp where you grew up?

HA: Within the camp itself, life was good. I always say I feel like I had a really great childhood. All the kids, we got along really well. We went outside, we got dirty, we played. Being in that environment, I learned not to seek materialistic things. I didn't value them. We valued friendship, because we were all we had.

The camp was very diverse. There were refugees from Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, and everywhere from Africa. It's funny, because our parents at first didn't really get along. I remember there'd be a lot of fights among the adults. There were long lines for water, because in our camp it wasn't every day that you had access to water. Sometimes somebody would push, and then you would see adults fighting. But the kids, we got along really well.

HB: What about school?

HA: Our camp had a little nursery school program, and my mom took me starting when I was four. She used to walk me there and wait for me. When it was time for me to leave, she'd be waiting outside for me. She didn't have to do that. A lot of parents didn't even bother to send their kids to the nursery school because they were like, it's a joke. My mom was like, “This is an opportunity and we're going to take advantage of it. I don't care who the teacher is, or if my daughter never learns past A-B-C-D, I'm still going to take her.” I remember getting my first report card. My mom actually brought it with her to America. As refugees, what you take with you says a lot about you, and that item. People don't take much with them. We didn't take clothes, we didn't take anything, but she somehow managed to protect that paper and keep it safe.

HB: Initially you settled in St. Louis, but then your family moved pretty quickly to St. Cloud, Minnesota. What were your first impressions of life there?

HA: When we came here, the thing I remember is that first winter. Everywhere I looked there was just white fluffy snow. That was something as a kid you hear, that in America it snows. You make up visions in your head about what that would be like, but you really have no idea. Kind of like when you read a book and picture it in your head…When people told me about snow, I just pictured the only thing I knew that was cold back home, which was ice cream.

HB: What are the biggest differences between your early childhood years in the refugee camp, and your childhood and adolescence since coming to the U.S.?

HA: Here, we tell kids all the time you can be anything you want. You can be a doctor, you can be a nurse. But over there, in the camps, it’s not the same. You don't hear as much of that “Be whatever you want to be” stuff. You just don't. Our parents, growing up, they had mountains of problems to face, and challenges they had to overcome. They had daily challenges as simple as food, shelter, and protection. They couldn't also worry about giving us hope. Organizations like the IOM, UNHCR, UNICEF, United Nations, all of them, they gave us food, shelter, and protection. But, unfortunately, hope is not something that is instilled in refugee children.

You didn't see people who were former refugees going back to the camps and telling the kids, “I've walked in your shoes before, and now I'm doing this.” As much as education and food and shelter are important, I think hope is equally as important. If not even more important, because children need to know that this isn't going to be their reality forever. They need to be given the freedom to dream, and to dream big.

HB: When did you become aware that you were “different” than other kids in St. Cloud, either because of your religion, or your foreign heritage?

HA: Middle school was a really hard time for me. The Somali population in St. Cloud grew, it felt like overnight. That created a lot of tension. Obviously, kids repeat what is said at home. I think that had a lot to do with it, because all of a sudden people were calling us “Smelly-ans,” and just awful nicknames. I went through a lot of teasing. It made me doubt who I was, it made me question a lot about myself and my identity. Things were just really confusing. Even the term African American—can I call myself African American? Those are things that are not explained to you in school, and obviously my mom was not going to sit down with me and talk about that. Why do I have black skin? What does it mean that I'm Somali?

That's something a lot of immigrant kids have issues with. Finding your identity, finding who you are, and still embracing your heritage. I was trying to find the balance of being Muslim, being Somali, being American, and at times it just didn't seem like those three things could all be balanced. My attitude was, I didn't wait for other people to do things first. When it was time for me to join after school programs, I didn't wait for another girl to do it with me, or another Somali. I just went ahead and I did what I wanted to do.

HB: You alluded to President Trump before. Can I ask you a question about his Muslim ban? We’re talking soon after Trump announced the latest version of that executive order, which prevents people from several Muslim-majority countries coming to the United States, including Somalia. As a Muslim and as someone who came to the U.S. as a refugee yourself, what is your response to Trump's Islamophobic rhetoric about how Muslim refugees are “dangerous” to the country?

HA: Well, I mean, take it from someone who is a former refugee, who is also Muslim: the last thing that refugees want is more violence and pain. They've had enough of that. They're running from that. When they get here, the first thing that they want is the same thing that my mother was after: to get their kids educated and to make a better life. They're not looking to stir up violence or to bring violence to the new place that they're going to call home. In my experience, refugees are the most loyal and patriotic people. I'm asked about Trump all the time. Even now, my mother is always telling me, “I better never hear you expressing anything but respect for the President.” That shows you how much she values this country. That's the attitude I grew up with all my life. You're never going to hear my parents’ generation complaining. “Poor us, Islamophobia”—no.

Now, I'm American. I grew up in this country. I'm willing to stand up for myself and say when things are wrong. It's sad, though, because our President should not be saying things like that. He should not be divisive. We are a nation of immigrants, that's something people forget. His family came to the United States as immigrants.

HB: His wife, too, is a former model and an immigrant.

HA: In a way, it's very sad that he holds these views, because that's not representative of our country. Unless you're Native American or Mexican, we're all immigrants. It was like when I grew up and people used to say, “Speak English.” Well, did the Native Americans tell you to speak Cherokee? I think it’s sad that some people forget their family heritage. They forget the time when their family experienced exclusion and suspicion. Muslims aren’t any different than other immigrants to America. These people are going to be your future teachers, educators, doctors. They are people who are going to put so much pressure on their kids to attend college so that they can give back to this country.

HB: What are your career goals beyond fashion?

HA: I feel like I'm starting to realize the power of this platform that I have thanks to my story. Just my Instagram page alone has the potential of educating people, by showing people what a Muslim girl my age is really like. One day if I have the opportunity, I would love to do TV or maybe film. To be honest, I will take whatever opportunity that comes my way.

Right now, I'm thinking why not try to grow within my partnership with UNICEF, because how amazing would it be to have a former refugee one day be a UNICEF global ambassador? I was talking before about hope, and I feel like that would instill so much hope for the children, to see somebody who lived in their circumstance in a position like that.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.